Biology

- Anatomy

- External Morphology

- Internal Structures and Systems

- Reproduction

- Ontogeny

- Evolution

Since the two species share the same name, they will be differentiated as inland Karraguls and coastal Karraguls. Despite having completely different forms of locomotion, they are very similar in practically every other way. Most major differences are superficial.

| Inland Karraguls | Coastal Karraguls |

|---|---|

|

|

ANATOMY

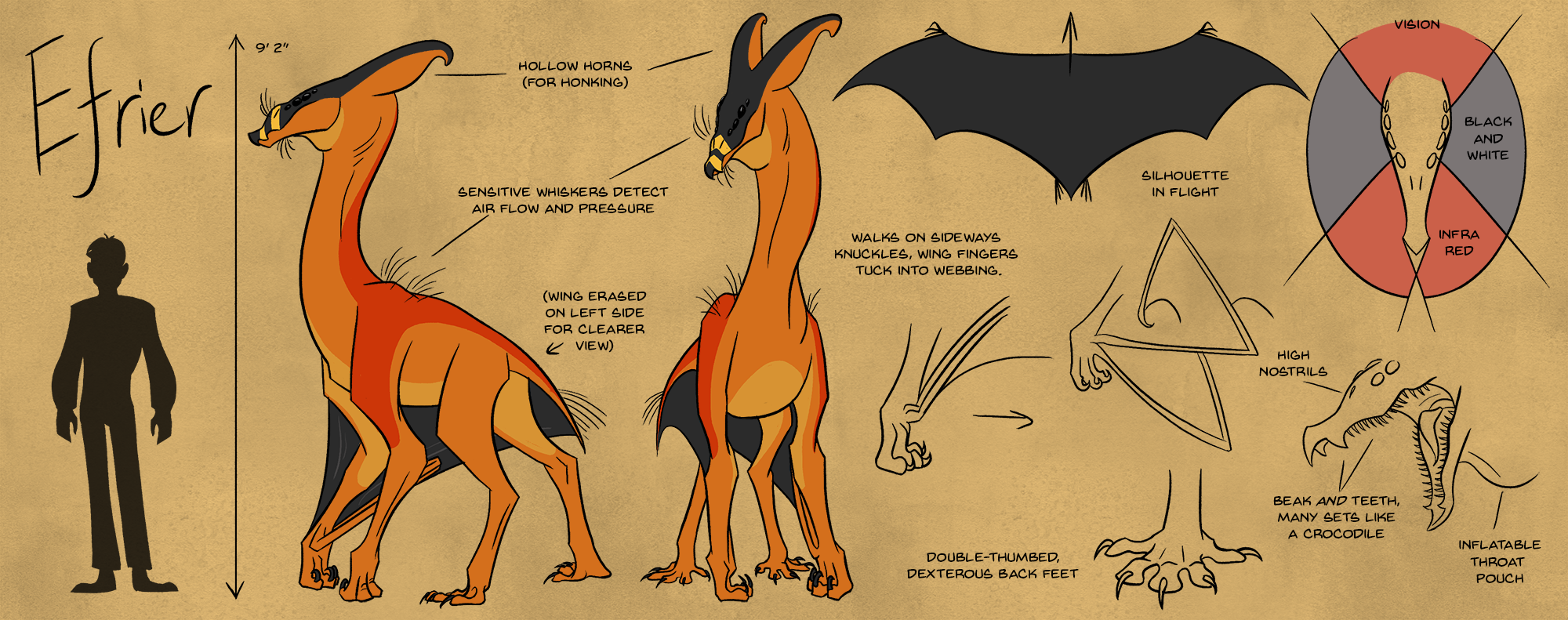

External morphology

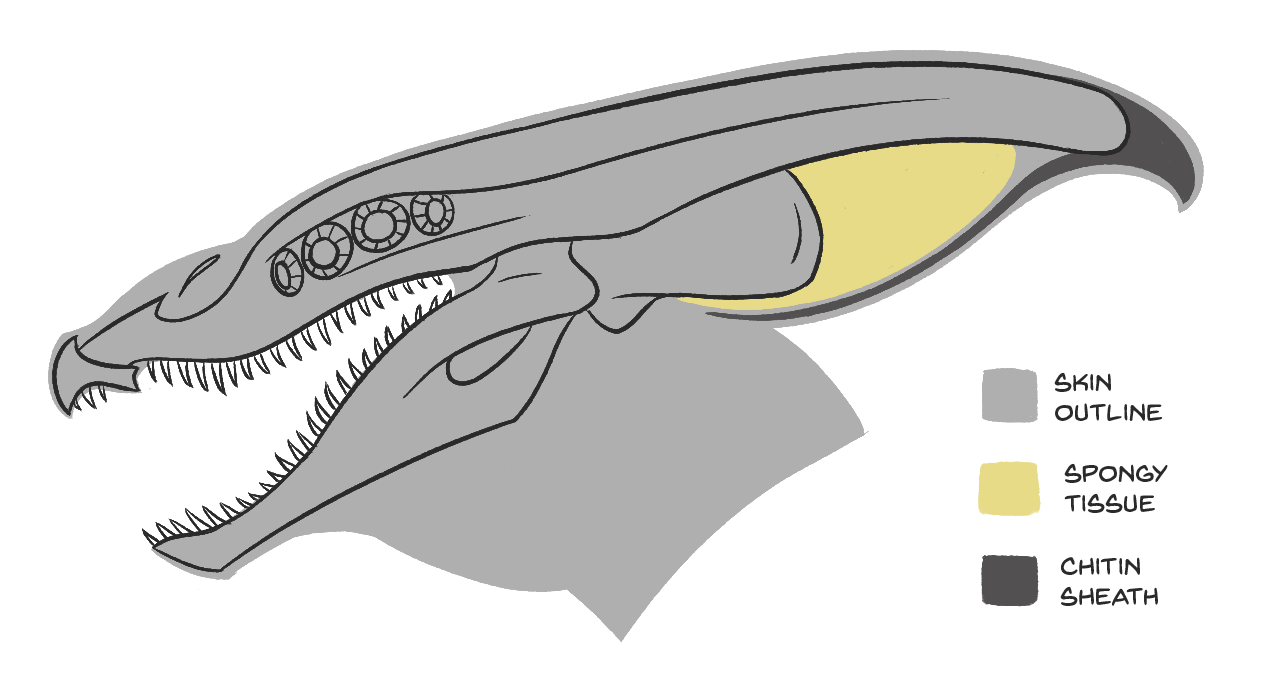

Head

Karraguls have elongated heads with 8 complex eyes – a row of 4 on each side – and nostrils positioned halfway up the face. Whiskers sprout vertically just in front of the nostrils and under the jaw. The mouth has a beak-like appendage, and is filled with needle-like teeth. They have dual hollow crests which resemble horns, which are normally curved with a characteristic “hook” at the tip. The length of the horns and snouts generally differ between inland and coastal Karraguls (see above), but there is great variation within each species as well.

After sexual maturity, the face develops black markings which vary highly between individuals and can be used as identifiers. Karraguls also have a throat sac.

Body

The back as a noticeable slope, with the shoulders much higher than the pelvis, and a tail that is angled downwards. Even in coastal Karraguls, which are bipedal, the slope is present and their long tails must be curled under the body to prevent it from dragging. Whiskers are present over the shoulder blades and at the tip of the tail.

Both species of Karragul are countershaded – having lighter bellies and inner limbs, and darker main bodies – but inland Karraguls also possess a red “cloak” that extends halfway up the neck, and runs down their back and their upper arms. Coastal Karraguls have cool skin colours in the purple/blue range, while Inland Karraguls are in the red/orange/coral range.

Wings

Wings consist of two fingers with dark webbing stretched between them and three separated fingers. In inland Karraguls, the knuckles are sturdy and used for walking, while coastal Karraguls’ have significantly lighter-built hands that are held at their sides. The palms face inwards. Although they are able to grasp things with these fingers, they're not as controlled or dexterous as their toes. The separate fingers are tipped with iridescent, chitinous claws, but the wing-fingers lack claws. These wing-fingers fold up on themselves and can be neatly tucked behind the webbing, so they're not visible when a Karragul is viewed from the side.

The webbing that makes up the wing attaches to the tail and partially obscures the legs. This webbing also allows for visual communication. Similar to a cuttlefish, they're filled with chromatophores that allow the Karraguls to flash rapid patterns to each other.

Legs

Feet possess two opposable digits, one on each side. They have a similar dexterity to human hands. Each toe has claws similar to the separated fingers.

Internal Structures and Systems

Senses

Karraguls have both infrared and monochromatic vision. The first and fourth pairs see in infrared, the middle pairs in black and white. They are able to see radiated heat from many metres away, and down several metres in loose substrate or water. The infrared vision is used primarily for hunter and predator detection, while the middle eyes are used to interact with other individuals e.g. watching the communicatory patterns on each other’s wings.

(Approximation of vision)

Their hearing range extends from 0-10kHz, meaning they hear what humans call infrasound, and their voices fall towards the lower end of that spectrum. Most of their long-distance communication is inaudible to humans, causing them to only feel vibrations and a sense of dread.

A sense of touch as humans would recognise is not really utilised. The feet have the most tactile corpuscles, but still less than a human. However, the whiskers are capable of detecting tiny changes in air flow, direction, and pressure, a great advantage to have while flying or at sea. A Karragul can sense an oncoming storm long before the clouds start to darken.

Their sense of smell is quite poor, with their sense of taste only slightly better. Out of the five recognised flavours, they detect salty and umami the strongest, and sweet the weakest. They also detect a sixth taste, which approximately equates to “freshness”. It is a flavour found only in the meat of living or freshly killed animals. This is thought to be linked to the presence of glycogen in the muscle, which rapidly degrades after death.

Sonic System

A Karragul's horns are actually not horns at all, but hollow crests connected to the nasal cavity. Karragul communities are often spread out over great distances, so they evolved loud, booming calls to communicate with each other. As mentioned above, they often utilise infrasound, which can travel many miles. They can also produce sound as a focused beam, which can stun or even kill small animals. Spongy tissue below the air passages help to concentrate the sound, and their throat pouches help amplify it further.

Reproduction

Sex

THIS SECTION IS STILL BEING WORKED ON AND WILL BE CHANGING.

Karraguls have a trisex, ditriploid system. Two sexes produce similar gametes and perform mutual insemination, while the third sex does not mate at all. Instead, they produce spore-like gametes that settle over already fertilised eggs. The third sex is generally responsible for guarding eggs and rearing offspring.

For most of the year, Karraguls are asexual. Unlike humans, there is only a small window each year they might be interested in sex. Up to a quarter of them do not develop interest at all.

Attraction

Though body and horn type preferences vary wildly between communities, there is one trait that is generally considered attractive for most Karraguls - a smooth, unbroken line between the black mask and the rest of the face. Most Karraguls have stripes of colour on their face unless they have a form of melanism, but the smaller the stripes, the better. A completely black mask with clear delineation is considered the height of beauty, and black makeup is often used to achieve this look.

Courtship

(Coming soon!)

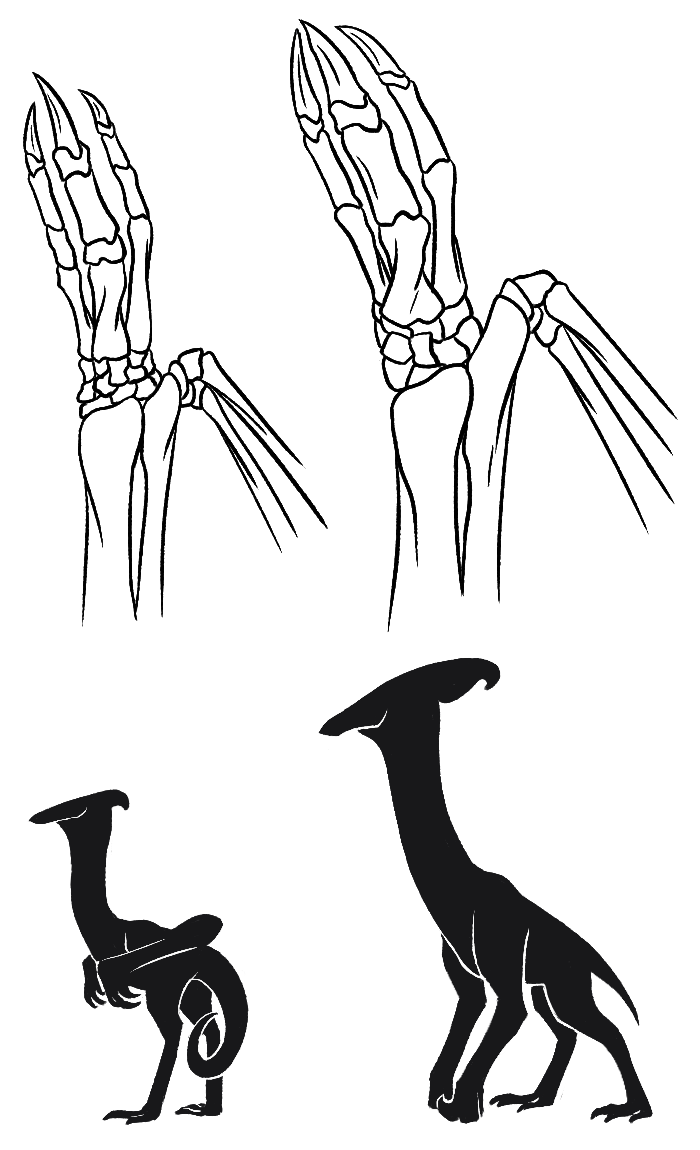

Ontogeny

Both species begin life similarly, and often cannot be distinguished by Karraguls themselves, as they do not see in colour. Bird-like in shape (apart from their long tails), they stand on two legs, having both short snouts and horns. They are able to walk after hatching, but cannot fly for a few months as they need to build up the strength in their forearms first.

During adolescence however, their development changes dramatically. In inland Karraguls, the crests rapidly increase in size, the upper body begins to bulk out, and part of the tailbone is reabsorbed. The change makes them top heavy, so much so that they eventually tip forward onto their knuckles. This transitional state means that teenagers are less mobile than babies or elders, and are often in a lot of pain. They are excused from most activities and cared for by the rest of the community.

Coastal Karraguls’ crests grow too, but not to such a pronounced degree, and the snout grows longer. Aside from proportional changes, their body plan remains more or less the same. Both species develop black facial markings as a sign of sexual maturity.

As they age, Karraguls tend to replace less teeth, and their skin colour will fade. Calls will also sound weaker and carry shorter distances as their lungs weaken, and the resonating tissue begins to degrade. However, crests strangely continue to grow as they age, straightening out as they do so and further affecting the quality of their calls.

Evolution

Karraguls and kin evolved from a group of amphibious creatures which became arboreal. Scaling the stems of fungi that grew in their watery habitats, their fins adapted to grasp first, rather than to walk on solid ground. The ability to fly also evolved in this group before they ever touched land, originally to help them glide between fungi.

There was a significant period of time where Karragul ancestors were both amphibious and able to fly, and it is likely their symbiosis with giant fungi first began here. When burst, the sporangium often fills with rainwater and could provide a cradle for eggs.